PLATTS

TEXTILE MACHINERY MAKERS

CIVIC LEADERS IN OLDHAM

COUNTRY SQUIRES IN NORTH WALES

R. H. EASTHAM

The Platt Coat of Arms

To Margaret, with thanks for immense help

Contents

Chapter I - The Starting Point — Henry Platt

Chapter II - Foundations Set - Hibbert & Platt

Chapter III - Elijah Hibbert and Hartford New Works

Chapter IV - Onward – Platt Brothers & Company

Chapter V - The Platt Brothers: John & James

Chapter VI - Settlement in Llanfairfechan — Bryn-y-Neuadd

Chapter VIII - Gorddinog — Colonel Henry Platt

Chapter IX - The Zenith of Platt Brothers & Company Limited

Chapter X - Evolution — Samuel Radcliffe Platt

Chapter XI - Inter-War Years - Public Company and Merger

Chapter XII - Consolidation and New Approach

Chapter XIII - The Finish of the Welsh Estates – Eric James Walter Platt

Chapter XIV - The Climax of Platt Brothers & Company (Holdings) Ltd

Chapter XV - Stone-Platt Industries Limited

Chapter XVI - The Final Era - Platt International, Platt Saco Lowell and Scragg Division

Preface

The creation of the greatest textile machinery making business the world has so far seen by a branch of the Platt family of Saddleworth and the rise to eminence of those Platts in Oldham and North Wales on the success of the business can be dismissed as yet another story of people having been in the right place at the right time. In ordinary terms such a view is true so I write in an attempt to tell the story in some detail from the beginnings in the eighteenth century to the days when the business had become a large international company and to show how the influence and vast fortune the business generated benefitted not only the Platts themselves but many others along the way.

Notwithstanding these aims, I have, in order to keep the story simple, included technical and financial details and dates only as they are necessary to explain turns of events and to align the chronicles of the several aspects of the story.

The circumstances of my life made it possible to learn the facts, at first hand, in North Wales, in Oldham, at the Company in Oldham and elsewhere and in Saddleworth. Nevertheless, I would be remiss in the extreme, if I did not acknowledge my profound indebtedness to those meticulous past historians of Oldham. Edwin Butterworth and Hartley Bateson, and to the late Ogwen Williams, one time archivist to the former Caernarfonshire County Council with whom incidentally, I was at school, and a host of others for the provision or corroboration of some of the detail pertaining to the earlier part of the story. My thanks are made to Gwynedd Archives Service, Oldham Evening Chronicle, Oldham Local Studies Library, Peter Fox of Greenfield and Lloyd Hughes, of Llanfairfechan, for the use of photographs from their collections.

Reginald Eastham

C. Text, ATI, MI Mgt.

July 1994

Chapter

I - The Starting Point — Henry Platt

Saddleworth lies on the western side of the Pennines. The courses of the upper reaches of the River Tame and its early tributaries score the moorland to form an exceedingly hilly district. In the valleys are dotted the principal villages: Denshaw, Delph, Diggle, Dobcross, Uppermill and Greenfield. In the mid-eighteenth century Saddleworth was a part of the former West Riding of Yorkshire and perforce, came under the jurisdiction of remote Wakefield on the other side of the Pennines’ highest and bleakest hills which separated Saddleworth front the rest of Riding. Its ready intercourse, therefore, had to be with the more accessible Lancashire, particularly the town of Oldham, some six miles distant, and Manchester where, more conveniently, it could trade much of its traditional woollen cloth. Ecclesiastically, Saddleworth had long been tied westwards: a chapel had been built in the district, early in the thirteenth century, of which St Chad, Rochdale, was the mother church, and had been incorporated in the diocese of Chester in 1541 (The Manchester diocese was not divided out of Chester until 1848. Because of its circumstances Saddleworth had imbued its people with strong senses of independence and self sufficiency; the Platts were of these people.

The Platts were of yeomen stock, traceable to 1334 — Robert de Platte connected with the Manor of Quick. Traditionally the yeomen in Saddleworth had gained a living from a combination of the tilling and grazing of their mediocre land with the manufacture of woollen cloth in and about their dwellings. By the mid. eighteenth century some were turning to farming their land in a more efficient way, in so much as the benefits of the Agrarian Revolution could he applied to their marginal type land, others were becoming engaged in the operation of small woollen mills which were replacing the traditional domestic cloth industry, others still, were serving the community as tradesmen in a variety of ways. The Platts had followed these trends. The nature of the Platt family’s participation in the social life of the community is shown from entries in the Saddleworth Parish Vestry Book: Edmund Platt was a churchwarden in 1752, similarly James Platt in 1758 and Joshua and John Platt, respectively, in 1764 and 1767.

(The early chapel had been superseded by the church of St Chad and Saddleworth had become a parish). The broad Platt family was scattered about Saddleworth but for the purpose of this story no useful reason would be served by proceeding to include a detailed description of the connections between those Platts on whom the story centres and the broad family though, shortly, a key relationship is mentioned from which the connections can be established.

It stands to reason, somebody had made the simple machines on which yarn and cloth were produced under the long practised domestic system. This had been done by local craftsmen, in an ad hoc way, as the machines were required, even by the intending users themselves if they had the skills. Basically, the machines — the age old carding board (a hand comb), spinning wheel and handloom — were constructed from wood, only a modicum of vital parts being fashioned from metal. But change was the order of the day in the second part of the eighteenth century and amongst the earliest changes, spawned by the industrial Revolution, was the factory system, born from the example set by Richard Arkwright, for the processing of cotton fibres. The concentration of textile manufacture in “mills”, as the factories were termed, called for a more powerful and constantly transmitted means of prime movement — because of the features of the terrain the water wheel predominated the horse in Saddleworth —and, in turn, the machines to be operated in the mills needed to be of a more robust construction to align with the more powerful means by which they were to be driven. Furthermore, inventions had been, and were being, made which the factory system could exploit: Flying Shuttle (Kay), Carding Machine (Paul), Spinning Jenny (Hargreaves), Spinning by Rollers and the Waterframe (Arkwright) and the Mule (Crompton) a machine which ‘crossed” the principles of operation of the Jenny and the Water- frame. Inevitably, such a situation could only lead to the emergence of the specialist machinery maker, who, moreover, would have to be more adept at working in iron, from which material a much higher proportion of the machinery’s parts had now to be made. One such, a blacksmith, was making at Dobcross, in 1770, carding machines for the

Smithy adjoining Bridge House, Dobcross where the Platt family first made textile machinery.

The building carries a commemorative ‘Blue Plaque’.

The creator of the textile machinery making business, at Uppermill, in

1815, which became, in Oldham, in 1822, the firm Hibbert & Platt,

1839— Hibbert, Platt & Sons, 1854 — Platt Brothers & Company,

1868 — Platt Brothers & Company Limited (Reincorporated 1898),

1931 — Platt Brothers & Company (Holdings) limited and in 1958 -

Stone-Platt Industries Limited.

growing number of local woollen mills. The name of the blacksmith was Henry Plat. He (christened on 17 December 1732 and James Platt (christened on 19 October 1729), the heir to John Platt of Butterhouse, were brothers.

Henry Platt’s smithy adjoined his dwelling, Bridge House. a property which still exists, bearing witness that it must have been necessary to cut away the stone door-jambs to permit large parts of the machines to be extracted for delivery to the customer. In due course, Henry Platt came to have the assistance of his son, John, who after Henry’s death continued to serve the local community, as blacksmith and farrier, whilst extending the range of the textile machinery he made to include ‘Billies” (a devise for preparing the strands of textile fibres, after carding, into a condition more convenient for spinning) and looms. In turn, John Platt was joined in the smithy by three of his sons, one of whom was his grandfather’s namesake. This Henry Platt, who had been born at Dobcross, in 1793, was a young man determined to prosper, so, towards fulfilling his ambition, he removed , in 1815, to nearby Uppermill where, in the building afterwards used as the Waggon Inn, he created his own business. The business was intended to concentrate on the manufacture of textile machines, for the ever increasing number and size of woollen mills in Saddleworth, on a scale which had not been possible in the smithy at Dobcross. But his sights were redirected when a business visit to Oldham resulted in his being asked, by a third party, to make a carding machine for a cotton spinner, in the town named Samuel Radcliffe, who, later, was to have close ties with the Platts. In Oldham the new cotton industry had already eclipsed the age old woollen industry and was still growing, to those of the time, at an astonishing rate. Moreover, Oldham did not have, as did some of the other Lancashire cotton manufacturing towns, a textile machinery maker of any standing. In Bolton, a firm which had been founded in 1790 could already offer the cotton spinner the comprehensive range of machines he required in his mill. The founder was an Isaac Dobson and the firm, alter bearing several names, settled, in 1850, under the name Dobson & Barlow. In 1821, after just six years at Uppermill, Henry Platt along with his wife Sarah (nee Whitehead of Saddleworth Fold) whom he had married, in 1815, at St Chad Church, Saddleworth, and their first two children. Joseph and John, went to Oldham.

Chapter II - Foundations Set - Hibbert & Platt

Henry Platt set-up his business in a house at Ferney Bank, which lay on Huddersfield Road, in the north-east quarter of Oldham. It was a three storeyed building, the family living on the ground and first floors with the workshop contained on the top floor. To the family, such an arrangement would be familiar and acceptable since the yeoman dwellings, in Saddleworth, had long been occupied in such a way, save in the case of these the top floor had housed the hand looms on which the traditional woollen cloth was woven. He employed five or six men to assist him in the making of his carding machines which were finding a favourable acceptance with the cotton spinners of Oldham. Alter a year’s progress, one week-end, he found he had not enough money to pay his workmen — in to—day’s jargonistic parlance he was beset with a cash-flow problem — and he hastened to seek a loan from a Mr Noton, a man in matters financial, to tide him over his dilemma. Unfortunately, Mr Noton was unable to help but he assured Henry Platt all was not lost as Mr Noton(was expecting, at any minute, a person who, he felt sure, would be able to help. The person duly arrived. he was Elijah Hibbert, hailing from Ashton-under-Lyne, but now living and successfully connected with several engineering undertakings in Oldham, Elijah Hibbert and Henry Platt quickly realised a mutual appreciation, not on1y was the loan furnished, but from their meeting there came into being, within that year of 1822, the firm of Hibbert & Platt. The firm was to be the most rewarding connection Elijah Hibbert was ever to make.

Hibbert & Platt had been founded in time to benefit from the second surge in the growth of cotton manufacture. In fact, it has been recorded that in the years 1824-25, Oldham was, of all the cotton towns of Lancashire, the one in which the industry grew the fastest. Bigger new mills and enlarged existing mills were now driven by steam engines and the spinning machinery to he installed needed to be of a still more sophisticated standard for which the prime elements of the construction required to be from cast and wrought iron. The inefficiencies of and the hostility to the power loom had been overcome and, after 1824, this machine rapidly supplanted the hand loom.

The house at Ferney Bank, Oldham, where Henry Plan first setup his home and business after moving from Uppermill.

The power loom opened up for the machinery maker a vast new market, reinforced by the fact that the Mule could become the supreme spinning machine since it was able to produce warp and weft yarns of sufficient strength, in cotton, for the power loom. (Previously, warp yarns had had to be of linen. In response to these developments, under the wider commercial experience of Elijah Hibbert and the inborn ingenuity of Henry Platt, together with the engineering skills and unstinted industry of both men, the firm of Hibbert & Platt steadily flourished. Larger premises had to be found, at nearby Mount Pleasant, where 5O men were soon employed. The growth of Hibbert & Platts business continued dramatically for its machines had found renown in wider Lancashire from where the volume of orders swelled the demands of Oldham. Simultaneously, the firm had attained the position of being able to supply cotton spinners with every type of machine they needed at that time; the firm had become comprehensive. By 1829 the call for larger premises was pressing again and these were found at not too distant, Greenacres moor, a locality which was becoming widely industrialised. The building acquired was a former cotton mill, around which there was space available for expansion, and it was given the name Hartford Works.

Progress at this new site bounded apace, as anticipated, the adjacent existing buildings were acquired and new buildings were erected to house workshops and foundries as Hibbert & Platt, in order to eliminate its dependence on others for the supply of the multitudinous parts for its product machines, concentrated the manufacture of the parts in its own hands, often, by methods of production it had itself devised and on equipment designed and constructed on its own premises. Textile machinery makers frequently found they had to pioneer methods of mass production well before other branches of the nineteenth century engineering industry found these to be necessary, or those branches of industry with which they are, nowadays, popularly identified even existed — a single Mule comprised hundreds of identical spindles. By 1839 the workforce had approached 400 people when, in that year, it was decided to admit as partners Henry Platt’s two elder sons, Joseph and John. These two young men had worked in the business from an early age and though their formal education had been simple, their knowledge of the business and the technical learning it had brought were profound. Resulting from this move the name of the firm was changed to Hibbert, Platt & Sons.

In 1842, a branch line of the Manchester & Leeds Railway had reached Oldham from Manchester. The terminus was sited at Werneth on the first level ground at the head of a steep gradient and immediately in front of the hill which divided some of the western part of the town from the remainder. At that time, Hibbert, Platt & Sons was again sorely confronted with the need to expand its premises — Hartford Works now employed in the order of 500 people — and it was projected to build an entirely new additional works close to the railhead. Meanwhile, the year 1842 was marked for the Platts by two significant events, one most joyous, the other extremely sad: John, the second son of Henry Platt, married Alice Radcliffe and Henry Platt died. John Platt’s bride — whom he married at St James Church, Greenacres, Oldham — was the daughter of Samuel Radcliffe to whom Henry Platt had sold his first carding machine for cotton, before he had left Uppermill. Samuel Radcliffe who, at the time, was a bourgeoning cotton spinner had prospered and was, now, one of Oldham’s premier mill owners. During the intervening years the two families had been close friends and neighbours, each had its residence close to their factories at Greenacres moor. Henry Platt died in the November of the year at the age of 49. He was buried at Hope Chapel, Oldham, as was his widow eighteen years later. Unremitting hard work had been the denominator to the time Henry Platt had spent in the far from healthy environment of the Oldham of his day and each had taken its toll. Moreover, fate had decided he was not to benefit from the vast new opportunity which was to open up in the following year. Yet, he had prospered, and, above all, he had been so mightily instrumental in giving Oldham its textile machinery maker of standing.

An Order in Council, of 1843, abolished restrictions on the exporting of machinery to foreign countries and Hibbert, Platt & Sons was not slow to take advantage of the opportunities presented. Soon, its machinery — now widely acknowledged to be of a high and unequalled quality — was being sold abroad on an accelerating scale, particularly after the new works, at Werneth, which had been named Hartford New Works, came into operation in 1844. The ability to export its products had on the business of Hibbert, Platt & Sons an impact which can be gauged from figures recorded, jointly for the two works, at the end of 1846. These figures showed the annual rate of usage of cast iron had risen by 113% to just short of 5000 tons, coal consumption had doubled at 1O 000 tons and, whilst the workforce at the original works had remained at 500 people the new works had engaged a force of 400, thus, in the space of two years the total workforce of the firm had risen by 80%. It is not surprising to find contemporary observers referring to “the great works of the firm”. Sadly, the colossal success of these two years was marred by two untimely deaths, that of Joseph Plan, in 1845, from consumption, at the early age of 30, and, in the March of 1846, that of Elijah Hibbert, at the age of 45. The deaths of both men served, yet again, as a sharp reminder of the detrimental effect the conditions of an industrial town, of that era, had on those who dwelt and toiled in it. James Platt, the younger of Henry Platt’s, now living, two sons (the youngest son, Henry, had died when a boy) took the place of Joseph as a partner in the business and, in due course, his brother John, who was now the senior partner, and he entered into negotiation with the trustees of Elijah Hibbert’s estate to acquire Elijah Hibbert’s interest in the firm. This move came to fruition in 1854, when the brothers Platt took into partnership the firm’s cashier and two heads of departments. From this course of events the firm assumed the name Platt Brothers & Company, the name by which it was to be known, with two minor additions, for over a century.

Chapter

III - Elijah Hibbert and Hartford New Works

The association with Henry Platt, from which derived their great firm, was, undoubtedly, Elijah Hibbert’s most rewarding venture. Yet he had been involved in other ventures which, at the time of his death, caused him to be considered Oldham’s most successful entrepreneur in the field of engineering. The esteem in which he was held, in the town, was expressed by the tribute paid at his funeral, of which an account says: the procession from his home, Lyon House. to Oldham Parish Church comprised, unsolicited, more than 300 of his workmen and some 150 principal inhabitants, including the clergy, magistrates and other authorities. He had been made a county magistrate in 1839 and in the year before his death he had become the chairman of the Oldham District Railway Company. He was Henry Platt’s junior by eight years, so that when they met, in 1822, be was only 21, yet, was launched successfully, on his own account, in an iron and brass foundry, at Greenacres moor, and in another part of the town, not far from where Hartford New Works was to be sited, he was in partnership with his uncle, a Mr Tomlinson, in a millwright concern. But his crowning glory was to come, in the premature evening of his life, from the leading part he played in the planning and commissioning of Hanford New Works.

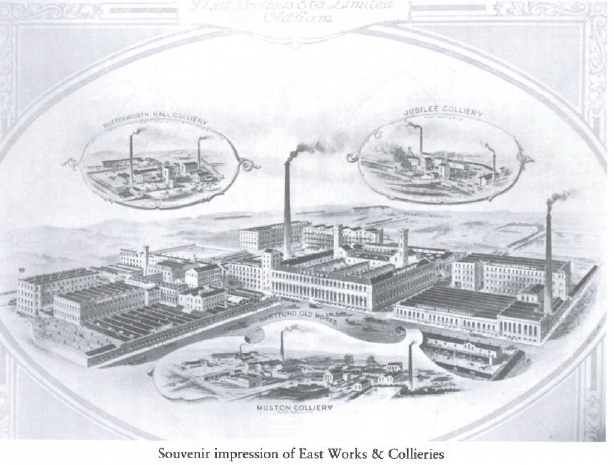

Hartford New Works was built, with its frontage on Fearherstall Road, on the north side of the railway with which it ran parallel down the gradient leading to Chadderton. Because it consisted entirely of new buildings the manufacturing plant was arranged, in the best possible fashion, to suit the types of machine it had been allocated to make from the firm’s overall range of products. Broadly, the machines which had been allocated were those which afforded the greatest degree of mass production methods to be used. These machines incorporated several lines of rollers (some precisely fluted on special purpose machine tools) running their full length and long ranks of identical production points — spindles. Generally, the frameworks were, comparatively, of a smaller and lighter nature which enabled the foundry facilities to be confined to a type most efficient for their particular production. Essentially, the allocation which had been decided meant it was the machines for the later end of the cotton spinning process which the new works was to make, which, moreover, were required in the mill in numbers greater than the heavier and bulkier machines comprising the earlier part of the process, the making of which was to remain at the original Hartford Works. (This allocation of the machines was, basically, to Continue until 1947).

In Hartford New Works the disposition of the work areas, machine tools and the arrangement of the line shafting system for driving them accorded with the best possible practice of the day — no doubt, Elijah Hibbert’s experience as a millwright had come into play. Hoists (lifts), passageways and stairways were positioned in the most efficient locations and care had been taken in arranging the lighting of the buildings; as much sky lighting as possible had been used. To administer, the Works was organised into departments, which, apart from the foundry, fell into two main categories, first those in which the various manufacturing operations (planing, shaping, milling, drilling, turning, polishing etc.) were performed on the host of parts which comprised the product machines and, second, those in which the fitters constructed the product machines. A foreman was placed in charge of each of the departments whose duty it was to superintend the work-force, at his disposal, and to ensure the work placed in his department was completed punctually and accurately. At the time of opening, the conception that was Hartford New Works led to it being acclaimed a showpiece engineering factory.

At this juncture, it might help if the simplest outline is given of the cotton spinning process, as it was, at the time the allocation of the product machines was made to the two works.

The first machines in the sequence opened and cleaned the cotton, taken from the bales in which it had arrived at the mill. The last machine, in this group (Scutcher), assembled the tufts of cotton, to which the hard pressed mass from the bales had been reduced, into a manageable rolled sheet (lap) for feeding to the next machine in the sequence which was the carding machine (Card).

The Card unrolled the sheet and fed the tufts onto the revolving cylinders, it contained, the surfaces of which were covered with wire points. Set close to the cylinder surfaces were other members of the machine, some of these also covered with wire points, others were equipped with knife-like edges. The combing and striking action thus caused on the tufts tore them apart allowing finer foreign impurities to fall out and, coincidentally, the fibre to be arranged to lie in a less tangled relationship. The machine assembled the fibres into a strand (sliver) which it delivered into a cylindrical can.

Manufacture of the foregoing machines was to remain at the original Hartford Works, at Greenacres moor. Although the Card was required in the mill in considerable numbers it included some heavy parts and, moreover, the cylinders, one of which was large, required foundry facilities alien to those which had been installed at the new works, at Werneth.

After the Card, the process was devoted to rendering the fibres in the strand more parallel, enhancing the regularity of the thickness of the strand and progressively reducing the thickness of the strand to that at which it was to be spun. These aims were achieved by passing the strand, which had issued from the previous operation, through a series of pairs of rollers, each pair revolving at a speed faster than that of the previous pair. (This was the essence of Arkwright’s invention, though his patent was contested on the grounds that he only harnessed a concept seen earlier by others. The machines which performed this part of the sequence were those which had been allocated to the new works.

The first machine (Drawframe) concentrated on making the fibres in the strand much more parallel and the strand, itself, much more regular in thickness. Normally, it did not reduce the thickness of the strand since a grouping of the strands from the Card (usually six in number) was passed through the pairs of rollers, the speeds of which were set in a ratio to draw the (six) individual strands into a single strand of thickness equal to that of the individual strands (doubling and drafting). The improved strand was, again, delivered into a cylindrical can. The operation was repeated according to the degree the fibres were to be rendered parallel and the degree of regularity required in the thickness of the strand.

The next series of machines — the Speedframes — continued the processes of doubling and drafting but the ratio of the speeds of the pairs of rollers was set such that the issuing strand was reduced to a thickness less than that of the strands led into the machines and nearer to the thickness the yarn was to be. The strand (Slubbing or Roving) produced on these machines was wound onto a bobbin, rotated on a spindle. The strand was fed to the first machine in the series (Slubber) from the cylindrical can produced at the Drawframe, subsequent machines, in the series, received the strand from the bobbin produced on the preceding machine.

The bobbin from the final machine in the preceding series (Rovingframe) was placed on the spinning machine (Mule). This machine, too, was equipped with rollers which, in fact, imparted the greatest amount of reduction in thickness to the strand to obtain the desired thickness (count) of the yarn. The yarn was formed as the strand received twist from the spindle onto which it was wound into a package (cop).

So perfect were the original inventions the process is little changed, in its essential elements, today.

Chapter

IV - Onward – Platt Brothers & Company

During the eight years between the death of Elijah Hibbert and the firm assuming the name Platt Brothers & Company progress was maintained at a phenomenal rate. The number of men employed rose from 900 to 2450, of which 750 were stationed at Hartford Works, Greenacres moor, and 1700 were stationed at Hartford New Works, Werneth. (The figures exclude boys). So expansive was the works at Werneth becoming, visitors, particularly from overseas, were astounded by what they beheld. The Company was now the largest employer in Oldham and the largest maker of cotton machinery in Lancashire and hence in the world. In attaining this status it had surpassed Dobson & Barlow, at Bolton, for so long the front runner in the business. From 1854 progress continued unabated so that by 1857 the company was able to offer the cotton manufacturing industry every type of machine it required for both spinning and weaving operations, an ability never to be matched by any competitor. Already, the dynamic leadership of John Platt was manifest, a leadership which was to become legendary.

John Platt had inherited the native Saddleworth ingenuity. He was the natural main spring for the Company’s continued exploration of the cotton spinning processes from the findings of which the techniques devised enabled the superiority of the Company’s product machines to be maintained. Patents were granted to him, often in co- ownership with members of his staff. At no time were John Plan’s innovative powers better demonstrated than during the cotton famine occasioned by the American Civil War. The spinning machinery in use in Lancashire had been prepared to process American fibre (staple) length cottons, but he adapted the machinery to process Indian and the other shorter fibre length cottons and averted for Oldham some of the distress the cotton manufacturing towns had had to endure. But that was not all, he developed machinery for the production of woollen and worsted textiles and so added to the Company’s range of products a line of machinery his forebears had originally set-out to make in a modest way. Platt Brothers & Company was now well on its way to becoming the undisputed, most substantial and comprehensive textile machinery maker the world has, so far, seen. John Platt travelled widely, not only as the Company’s premier salesman, but with an eye open for opportunities to exploit the local scenes and, in turn, of course, to holster the fortunes of the Company. The cotton ginning machine marked a significant example of such a policy when it was introduced into the Company’s line of products. The cotton ginning machine (Gin) is not used in the mill but in the cotton fields leading, in some instances, to it being classified as an agricultural machine. This machine separates the cotton fibres from the pod (boll) on which they grow, the pod having been handpicked from the plant. The machine in the “saw” form was invented in the USA in 1793, by Whitney and, later, McCarthy invented the “roller” form which did not damage the cottons with the longer (staple) fibres. Platt Brothers & Company was to make both forms; for manufacture they were allocated to the original works at Greenacres moor. Very quickly John Platt’s powers of invention were applied to the Gin for in the early eighteen-sixties he was filing applications for patents concerning the machine.

The combination of the enlarged range of products and the ever escalating volume in which they were being sold caused the workforce to rise, by 1872, to a total of 7 000. A growing number of the machines sold were replacements for the earlier, comparatively, primitive and less productive versions and the manufacture of power looms was approaching 300 machines per week, the greater part of which was destined for markets overseas. A loom fitter and his apprentice were required to build three looms every two days; it used to be said that all a loom fitter needed was a lead hammer and a stout pair of clogs. Yet the sheer increase in the size of the workforce was not the only measure taken to meet the fortunate demands the Company had placed upon it. The Company maintained its policy of concentrating, within its own hands, the manufacture of the component parts it needed for its machines, which were now vast in number and variety and made from an assortment of raw materials. So, in order to minimise the time taken to produce the parts, more and more machine tools and refined production methods were introduced. Again, to achieve this end, some of the machine tools were designed and manufactured by the Company on its premises. Tool Rooms, millwrights and general maintenance departments had become permanent establishments within the Company. So intense had the policy of self-sufficiency become, every nut, bolt and screw was made on the premises and, even, the taps and dies by which they were machined. (Although the screw threads were of Whitworth form the specification was the Company’s own and the items were identified by a numbering system peculiar to the Company Platt’s No. 1, Platt’s No. 2, Platt’s No. 3 etc.). The nuts, bolts and screws were but one example of the second string to the bow of the Company’s policy, namely to tie the customers to Platt Brothers for spare parts. Eventually, virtually the only items the Company was to bring into its works were the raw materials and it was this approach to self-sufficiency, and the scale of the production capacity it generated, which astonished visitors.

Both Works came to have direct access to the railway after the line had been extended from Werneth into the heart of the town. (Tunnels had been driven through the hill, at Werneth, by the, newly formed, Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company in 1847). The town’s new main station had been sited at Mumps from whence, in due course, the line was extended via Shaw, Newhey and Milnrow to Rochdale. At a point shortly after leaving Mumps, for Shaw, sidings had taken off the line to form Hartford goods yard and from this goods yard a private line continued, across Derker Street, into the Company’s Hartford Works. The sets of private railway sidings installed at the Platt Brothers & Company’s two works were, by far, the most extensive in Oldham, that at Werneth being virtually a miniature railway in itself. In fact, the siding at Hartford New Works was a loop line which left the main-line, from Middleton Junction, at a point on the gradient, which ran alongside the Works, and re-joined at Werneth Station. From the loop line sidings fanned out all over the Works on which the Company’s own stud of 0-4-0 rank locomotives busied themselves shunting in waggons of raw materials and drawing out vans and waggons laden with the Company’s product machines. Similar shunting, operations, on a somewhat lesser scale, took place, with some more Company owned locomotives, at the original Hartford Works. The Company possessed a fleet of private owner waggons which, together with the locomotives, were serviced by the Company’s own maintenance departments (millwrights and Joiners). John Platt had been an ardent supporter of railways to connect Oldham with the remainder of the country. The London & North Western Railway Company had brought a line, via Saddleworth, from its main Manchester to Huddersfield line and the Oldham, Ashton & Guide Bridge Railway had connected the town with the south. Platt Brothers & Company had, therefore, obtained ready routes to its customers in Lancashire, Yorkshire and farther afield and, particularly, to the ports on both the west and east coasts of the country. John Platt was a director of the London & North Western Railway and the Chairman of the Oldham, Ashton & Guide Bridge Railway, having followed Elijah Hibbert in that office of the (renamed) company.

The Great Exhibition, at the Crystal Palace, in 1851, and the exhibition in Paris, some four years later, were, for the Company, excellent shop windows from which much business resulted. At the London exhibition the Company’s machines were adjudged to have excelled all others in their class, for which achievement the Company was awarded the Council Medal. At Paris similar success attended the Company’s exhibits resulting in the award of the Grand Medaille d’Honneur and, from the Emperor Napoleon III, personal honours for John Platt in his elevation to the rank of Knight of the Legion of Honour. Throughout the eighteen-sixties and into the early seventies the Company’s machinery enjoyed further success at a number of exhibitions: London, again — Prize Medal, Constantinople — Order of Medjidie (for Gins), Naples — Silver Medal (for Gins), Paris, again, — Gold Medal and Moscow — Gold Medal. The renown of Platt machinery was now as universal in Europe as it had been in Lancashire some thirty years earlier and the successes at these exhibitions served unfailingly to uphold the renown.

John and James Platt had, from the outset of their tenure of the Company, encouraged their workpeople to elevate their social and intellectual interests, as later they came to do for the population of Oldham at large. As early as 1848, they established a library for the use of their workpeople which, initially, was stocked with 500 volumes of sound educational material with the promise to add, each successive year, a further 50 volumes. They also instituted a newsroom which was supplied with the national and leading provincial newspapers, for the use of which a workman paid one penny per week. But 1851 was to see the first strife between employers and employees in the engineering industry in Oldham. The introduction of the ever increasing number of machine tools caused the skilled workmen to dissent as more and more unskilled labour was recruited to man the machines and, eventually, matters came to a head in a strike which lasted for several months. The Society of Operative Engineers, the trade union representing the skilled men, resolved on a trial of strength with the employers and endeavoured to enter into negotiation with them but the employers countered by forming their own federation — believed by the Union to be a move instigated by John Platt — and, in due course, some employers decided on a lock-out, though Hibbert, Platt & Sons (as the company was still named at the time) did not follow this course as urgent orders for Russia were in hand. Both sides were to experience losses hut ultimately the workmen suffered the most and, finally, were forced to succumb. Although some rancour resulted it was not long before it dwindled away when the workmen realised that because trade was flourishing, on a scale never before experienced, plentiful employment was readily available for all grades of labour at good rates of wages. During the strike the news room was destroyed and the library was closed for its protection. However, soon after the troubles were over the Company re-opened both facilities, the library then to contain in the order of 5 000 volumes.

It has been said that the Platt machinery was the true basis of Oldham’s industrial supremacy. By 1871 Oldham, alone, had more spindles in operation than any one country in the world had in total, save only the USA. Although the Company had experienced, from its outset, competition from other textile machinery makers based in Manchester and some of the other Lancashire cotton towns it had had from 1843 a not insignificant competitor situated directly in Oldham; this was the firm of Asa Lees. The Asa Lees business, housed in premises named Soho Works, was located at Greenacres moor, on the opposite side of Huddersfield Road to Platt Brothers’ original Hartford Works, and had grown from the roller and spindle making business which Asa’s father, Samuel Lees, had founded in 1816. Both firms had prospered, to the general good of Oldham, although Asa Lees had never equalled nor ever was to equal the scale and scope of Platt Brothers; the Asa Lees’ workforce, at its greatest, only reached a quarter of that of Platt Brothers. From 1871 the sustained demand for textile machinery in Oldham saw Platt Brothers supply slightly more than three times the amount of machinery supplied by Asa Lees and in the markets elsewhere at home and overseas the amount supplied by Platt Brothers was at an even higher ratio as Asa Lees, a cautious man always, preferred to limit his commitments especially to the export trade. Though not as comprehensive as Platt Brothers, Asa Lees was a sound concern in the manufacture of those textile machines it elected to make and in the markets where it chose to operate.

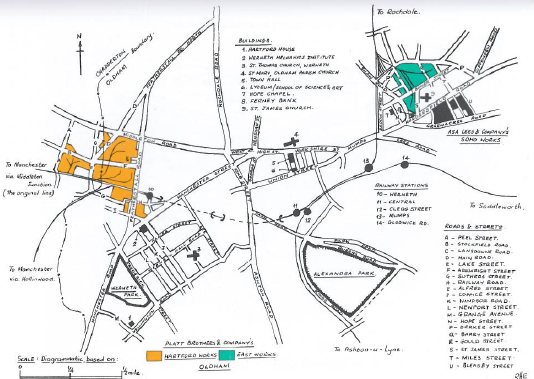

Pursuant to the Companies Act of 1862 Platt Brothers became, in 1868, a limited liability company. In time, the head office was transferred to Werneth, the name of the works there dropping the word “new” to become Hartford Works with the original works, at Greenacres moor, being renamed East Works. But the vernacular, as it always does, had long found the succinct nomenclature, it had opted or “t’new end” and “th’owd shop”.

Chapter

V - The Platt Brothers: John & James

John was a name regularly bestowed by the Platt family on its sons, but this John Platt was, to the people of Oldham and, in due course, Llanfairfechan “The John Platt”: industrial magnate, civic leader and public benefactor in Oldham, the town’s mayor and Member of Parliament and Justice of the Peace for and Deputy Lieutenant of Lancashire, country squire and benefactor in Llanfairfechan, Justice of the Peace for Caernarfonshire, Deputy Lieutenant and High Sheriff of that county. He was the one member of the family to tread all the stages of the Platt metamorphosis. Albeit, he was only four years old when taken by his parents from Saddleworth to live in Oldham, but his first experiences must have been of Dobcross, his birthplace, and of the wider Saddleworth surroundings and traditions his forebears had known for generations. Moreover, there is record that John Platt returned to Saddleworth for some part of his formal education. It was to the boarding school run by Ralph Broadbent, assisted by his brother Charles (an accomplished mathematician), in a house, “Springhill”, on Hey Flake Lane above Delph Heights. There is mention that James Platt also attended this school. James Platt was a native of Oldham. He, too, applied many of his energies to serving his fellow townspeople. He was a member of the Borough Council, was associated with many social and cultural projects in the community and, even, preceded John as Member of Parliament for the Borough before a grievous fatal accident brought his works to an end. All this devotion to public service the brothers undertook, in parallel, with the stupendous feats they achieved in directing and developing the great company which bore their name and of which they were the virtually exclusive owners.

In entering public life the Platt brothers contrasted with Henry Platt, their father, who seemed to have left that realm to Elijah Hibbert. There is, even, record of John and James’ older brother, Joseph, speaking at one of the meetings called to support the petition for Oldham to be granted the status of Parliamentary Borough. By the time John Platt became involved in public affairs Oldham had been granted its two Members of Parliament and the burning issue then before the town, in 1848, was the question of a Charter of Incorporation.

Opinions in the town were viciously divided. John Platt was strongly in favour of a charter and came to be the leading spokesman for those of similar persuasion, known as the Charterites, He voiced the dissatisfaction felt over the way the then authorities (Police Commissioners) were administering, or not administering, the town. Prime amongst the complaints were the lack of upkeep and control of the streets — Union Street, the main thoroughfare, he condemned as frequently being ankle deep in mud — the market traders were allowed to erect their stalls in the streets haphazardly to the general inconvenience of everyone else and, above all, the unsatisfactory water supply and sanitary arrangements were a cause for great concern. Many heated meetings occurred, at one such in the Town Hall, John Platt withdrew from the chair when proceedings fell into total disarray. Ultimately the Charterites prevailed, a Royal Charter was secured and Oldham became a Corporate Borough in 1849. John and James Platt subscribed their names to the list of persons guaranteeing to meet all the expenses incurred by the Committee which had promoted the Charter. (Their joint promise was for £100, almost one quarter of the total sum guaranteed). The first elections to the Borough Council were held in the August of 1849. John Platt was elected to represent St. James’ ward which contained that part of the town in which the original Hartford Works stood. In 1854 he was made the (fourth) Mayor of Oldham, an office he was to hold twice more in 1855-56 and 1861-62. In the year he first became the Mayor he was joined on the Borough Council by James who had been elected to serve the Westwood Ward, in the north-western corner of the town in which Hartford New Works chiefly stood. From its inception the Oldham Borough Council moved quickly to rectify the shortcomings the Charterites had proclaimed.

In politics, the Platt brothers were Liberal, in fact, they subscribed to the beliefs of the radical wing of the party; for many years John Platt was the chairman of the Oldham Radical Committee, in matters of free trade they were disciples of Cobden and Bright — John Platt had been active in the campaign for the repeal of the Corn Laws, they supported household suffrage — in this connection John Platt was President of the Oldham Freehold Society, short parliaments and the total abolition of church rates and all oaths, tests and religious disqualifications. Particularly they were in favour of education for the working classes; it has been seen already that they had taken practical steps in that direction for their own workforce before they became involved in the wider provisions in the town. In Oldham parliamentary politics the brothers were a strong force, for instance, when during the campaign for the 1847 election John Fielden — one of the retiring Liberal members — split the Radical ranks, in insisting it was his prerogative to select his running partner, John Platt powerfully supported William Fox who had been selected, as a third Liberal candidate, by those Radicals sorely exasperated with Fielden’s attitude. Fox was elected (in partnership with John Duncuft) to the exclusion of Fielden. In 1857 James Platt became vitally involved in parliamentary politics when he was elected a Member of Parliament for Oldham, in company with J M Cobbett. John Plat, delayed his candidacy until 1865, when he was successful, which process he repeated in 1868 and remained an MP for Oldham until his death. On both occasions he was elected in company with J T Hibbert. John Tomlinson Hibbert, later Sir John Hibbert KCB, was the eldest son of Elijah Hibbert. He was born at Lyon House, Oldham, in 1824 and educated at Shrewsbury School and St. John’s College Cambridge. He was called to the Bar in 1849 and, in all, was MP for Oldham seven times. He was, also, the first chairman of the Lancashire County Council.

Towards fulfilling his belief in the need to educate the working classes, John Platt lent his support to the Mechanics Institutes in and about Oldham. These Institutes had been established, by popular demand, to impart to artisans, chiefly engaged in engineering, elementary literacy and the basic mechanical skills. He played a leading part in the provision of the new building to house the Werneth Mechanics Institute which, originally, had operated in a Sunday School room on Windsor Road. The new building was erected on the corner of Manchester and Coppice Streets and after it was opened, by William Ewart Gladstone, in 1867, the Platt Brothers’ apprentices were sent there to receive, each week, a half day’s course of instruction.

However, the principal establishment in Oldham concerned with the betterment of education was the Lyceum. To the furtherance of this establishment both John and James Platt made notable contributions. The Lyceum had been founded, in 1840, as a mutual improvement society for working men. At first, meetings were held in premises in Henshaw Street but shortly afterwards a move was made to Queen Street where a library, newsroom and reading room were installed. In 1854 James Platt, who by then had been elected President of the Lyceum, resolved a superior building was required and he planned and organised, in the Working Men’s Hall, an exhibition, of scientific, historical and cultural items, loaned from all over the country, to raise funds for such a building.

The event proved an out-standing success, enabling the foundation stone for the new building, situated on Union Street, to be laid by James Platt himself in 1855. The new building was opened a year later when the curriculum of the Lyceum was extended to include classes in scientific and cultural subjects for which, initially, the teachers gave their time free. The new building was topped with a splendid observatory, the telescope for which was the present of James Platt. Later, John Platt offered the Lyceum a collection of equipment to found a permanent school of science and art, provided the facilities were thrown open to the residents of the wider Oldham area, irrespective of their being members, or not, of the Lyceum. The school, housed in a building next door to the Lyceum, was another success. In accordance with John Platt’s wishes it offered classes in mathematics, applied mechanics, chemistry, drawing, and in Latin and French. After John Platt’s death his sons had the original building demolished and erected, in its stead, a new building, adjoining and in the style of the main Lyceum building, as a memorial to their father. The new building was opened by the Earl of Derby in 1881.

During the period of the cotton famine, John Platt was deeply concerned to prevent the workforce of Oldham from leaving the town, for emigration to the USA and Australia was seen by many of the unemployed as the solution to their plight. It has been seen what he under took in his own sphere, textile machinery, to avert such happening but, also, he constantly warned that emigration was fraught with disaster and seized on adverse reports, on the experiences of those who had taken the step, to stress his warnings. At a public meeting he stated “Letters have been received from persons who have emigrated to Queensland which are most discouraging. Employment is said to be scarce, and their families are advised not to come out and starve. Naturally, he supported the scheme to use the unemployed to build a public park in Oldham (Alexandra Park), which apart from the immediate advantage it offered, he and his brother James had always thought desirable. When the first abortive attempt to create a park was made, in 1846, Hibbert, Platt, & Sons had donated £60 to the fund which, unfortunately, had fallen short of the required total. Periodically, each had lamented the lack of progress towards creating a park. James Platt, when speaking at a dinner, in 1853, expressed his view that the difficulty lay in the fact, that at the time of the Enclosures, the town had had no bona fide municipal authority to gain land for public purposes. On the day Alexandra Park was opened —28 August 1865 — John Platt is reported to have said “The noblest bequest that had ever been given to Oldham had been opened that day”.

In the eighteen-forties, those industrialists who could afford to do so were moving to a place of residence away from the immediate vicinity of their factories. John Platt certainly could afford, as could Samuel Radcliffe — his father-in law, Josiah Radcliffe and Eli Lees — a cotton spinner and weaver and brother of Asa Lees. In partnership, in 1847, they acquired an area of land in Werneth which had been the estate and site of the ancient manor house of the Oldhams of Oldham. This Land they laid out as Werneth Park in which each built a new mansion, the most superior, perhaps, Oldham was ever to see within its boundaries. John and Alice Platt had thirteen children, seven sons and six daughters. By 1851, five of the children had been born, the eldest, Henry, being eight years old and, together with a governess and four servants they were established at the mansion. Ten years later, although the older boys were now away at school, the family and the household comprised John and Alice Platt, seven of their children and fourteen servants. The eldest daughter, Mary, now a young lady of seventeen, divided the two oldest boys: Henry and Samuel. At first, John Platt had strong intentions that his sons were to receive a useful and practical education, whereupon, the two oldest boys were sent to Cheltenham College, where the curriculum was directed towards imparting modern commercial knowledge; the classics were not studied. From thence they proceeded to the Friedrich Wilhelm Real Schule in Berlin. On return to England, Henry went up to St. John’s College, Cambridge, whereas Samuel went directly into the works at Oldham. Thereafter, John Platt seems to have changed his ideas, the third son went to Harrow and the other sons, too, were to follow a conventional English education commensurate with the status the family had now achieved. James Platt and his wife, Lucy Mary (nee Schofield) took up residence at Hartford House, on the nearby corner of Grange Avenue and Wellington Road: they had one child, a daughter, Edith.

At the beginning of the eighteen-fifties the brothers took the step which industrialists, as successful as they were now taking, namely, to acquire a country estate. Jointly, they bought the Ashway Gap estate which lay above the Saddleworth village of Greenfield. The house stood in the sheltered Dove Stone Clough but this John Platt

commissioned to be replaced with a new house, Ashway Gap House, a property of considerable size partly in the castellated style. Had not a tragedy occurred this estate might have remained their country seat. Shortly after the opening of the grouse season in August 1857 James Platt was shot and mortally wounded when one of the guns was accidentally discharged as the party crossed a gully on the high hills, known as Ashway Moss, above the House, he was only 33. James Platt was buried in the new cemetery at Chadderton which had only been opened on the first day that of August. Ironically, he had been a member of the Board which had overseen the cemetery’s preparation and opening. On the fatal spot, itself, a monument was erected in his memory which throughout the years, the Company kept in repair against the ravages of the weather on that exposed spot. The monument carries the inscription: “Here by the accidental discharge of a gun James Platt MP for Oldham lost his life 27 August 1857”. John Platt came to an arrangement with his sister-in-law (who was only to survive James by five years) under which he obtained from her James’ share in the Company, his own share in the Ashway Gap estate constituting part payment for such, with the result, for all effective purposes, John Platt became the sole owner of Platt Brothers & Company.

Chapter

VI - Settlement in Llanfairfechan — Bryn-y-Neuadd

It was in Llanfairfechan that John Platt decided to create his fresh country estate. Llanfairfechan is a village which lies on the southern shore of Conwy Bay at the point where the Menai Strait opens into the bay and, hence, is near equidistant between the town of Conwy and the city of Bangor. In the mid-nineteenth century it was in the former county of Caernarfon and had a population of some 8OO inhabitants who, as small tenant farmers and peasant folk, followed a way of life which had scarcely changed in generations. When, in 1857, John Platt found Llanfairfechan he had missed the opportunity to acquire the Bulkeley lands of which, just twelve months earlier, Sir Richard Bulkeley, whose main estate was across the Strait in Anglesey, had decided to dispose. The sale of these lands, which had been in the Bulkeley’s possession since the sixteenth century, had already brought changes in Llanfairfechan the more enterprising of the local people had bought the land they farmed and others had obtained a plot of ground on which to build a boarding house to cater for the increasing number of visitors, chiefly form Manchester, Liverpool and other Lancashire industrial towns, who were finding Llanfairfechan, with its sandy seashore and hills, a congenial place in which to pass their summer holiday. But the principal purchaser of the Bulkeley lands had been a Richard Luck, a wealthy Leicestershire solicitor, who developed his purchase into a neat little estate on which he built an adequate mansion and named “Plas Llanfair”. John Platt had to turn his attention to lands on the western side of the river (Afon Ddu, flowing through the village, south to north) which for centuries had belonged to a family named Roberts. The last of the Roberts line had died in the latter part of the eighteenth century and the lands had passed to his daughter, Mary, and thence through marriage to the Wvnne family of Denbighshire. Mary’s son, John Wynne, had, in 1832, impoverished himself when endeavouring to replace the Roberts’ old house, Bryn-y-Neuadd, with a new mansion. John Wynne had been forced to sell his entire Roberts possessions in Llanfairfechan to a resident of Bangor who had made no attempt to complete the mansion so that, in its unfinished state, it had lain derelict and decaying for twenty-five years. John Platt bought Bryn-y-Neuadd and the former Roberts lands and, very soon, the astonishment the local people had felt at the Richard Luck development was to pale against their utter disbelief at the vast transformation John Platt was to bring about in their simple part of the world.

The new Bryn-y-Neuadd estate was to be created in the classic style: park with carriage drives and walks, gardens — including a walled kitchen garden, coverts and copses, stables and coach houses and a home farm. Work proceeded at a speed and with an intensity as if a rural Hartford New Works was being fashioned from the Welsh countryside; in just four years the transformation of the former Roberts possessions was completed. The House had been enlarged to four times the size John Wynne had envisaged, John Platt had gained permission to move the line of the Turnpike road, in order to take it further away from the House, and the fringes of the Park were planted with trees to screen the House from both the road and the railway. Along the shoreline, a sea wall was constructed, surmounted with a private promenade which was approached from the Park by way of a private level crossing over the railway and a drive in a secluded avenue. Two principal lodges controlled entry into the Park: Front Lodge which stood on the Turnpike road, at a short distance from the centre of Llanfairfechan village, it bore the date 1861 and was adorned with the Platt coat of arms and family motto “Virtute et Labore”. Grand lodge, a building which was arched over the carriage drive, at the far end of the Park, was used for joining the Turnpike road for journeys westward towards Abergwyngregyn and Bangor. A third, lesser, lodge controlled passage to and from the railway station and Farm Lodge stood at the entrance to the home farm. The Annals of the County Families of Wales described Bryn-y-Neuadd, “the seat of John Platt Esquire” as “a structure which with its appurtenances, tastefully planted grounds and magnificent surrounding scenery is one of the most pleasing residences in the Principality”.

John Platt was not to let his new estate rest within the boundaries of the Roberts lands, he bought-up the adjoining small farmsteads from which the primitive buildings were swept away and the land itself was converted into large fields to increase the acreage of the home farm which had been functioning from 1858 — quick time even by John Platt’s standards. On some higher ground a subterranean reservoir was constructed to secure an adequate water supply for the home farm and the estate generally. In his dealings John Plats was forthright and had no time for others who did not behave likewise, as instance the occasion when the contract for the purchase of one of the adjoining farmsteads was to be signed. John Platt had the pen in his hand when the vendor started to quibble the price which had been agreed. John Platt threw down the pen in disgust splattering the document with ink. The document remained in that state and Wern Farm never did become part of the Platt estates, it was left, oasis like, in their midst.

It has been said the Llanfairfechan that came into being in the mid- nineteenth century was a product of the Industrial Revolution, though patently not in the usual sense, but certainly John Platt’s presence in the place brought a degree of prosperity and opportunities far beyond most of the inhabitants’ previous understanding. Besides those people who raised capital from the sales they made to John Platt many more benefited from the considerable and varied forms of employment he generated, stonemasons, in particular, had never imagined such a scale of building as John Plan set in train. A few Llanfairfechan men moved to Oldham to take up employment in Platt Brothers’ works, a move occasionally to recur throughout the time the Platts had their estates in North Wales (John — “Johnnie” — Hughes, the redoubtable Works Director of the nineteen thirties, hailed from the neighbouring village of Abergwyngregyn, he was the son of Colonel Henry Platt’s head coachman). In the earlier years, several young women also made the move into Service at Werneth Park. Certain of those local people who had raised capital used it to finance more new boarding houses and shops two of which, in tribute to the “great man”, as they referred to John Platt, were given the names “Manchester House” and “Oldham House”. John Platt’s own riches were taken to be infinite, even as late as the nineteen-thirties some very old people in Llanfairfechan, most of whom were only Welsh speaking, used, graphically and sincerely, to recount: “to the station, trains with the gold of Mr John Platt were coming”. Then, just when it seemed the boundaries of John Platt’s new country estate had been drawn he, at a stroke, more than doubled his Welsh landholdings when he bought the estate which bordered on Bryn-y-Neuadd. This estate was Gorddinog of which only a part lay in Llanfairfechan, the rest was in Abergwyngregyn, commonly known, for short, as Aber. Immediately, the original House was razed and a superior one erected in its place. In 1869, Henry Platt, who, it has been seen, was John Plan’s eldest son, with his recent bride, Eleanor, took up residence in the newly completed mansion at Gorddinog.

When John Platt settled in Llanfairfechan the village had no railway station. The Chester & Holyhead Railway Company, which had opened its line, in 1848, had missed out Llanfairfechan when allocating stations along the route, although Penmaenmawr, to the east, and Aber, to the west, had been favoured. Speculation has been made that Llanfairfechan was ignored because no person of consequence resided in the place. Be that a valid explanation or not, the absence of a

railway station at Llanfairfechan was soon remedied by the now person of consequence who, other factors apart, it will be remembered, was a director of the London & North Western Railway Company. The Chester & Holyhead Railway Company had never possessed engines and rolling stock of its own, from the outset, the trains had been operated by the London & North Western Railway. The station at Llanfairfechan was stone built, making it superior to the other stations along the line, and was positioned as near as it could possibly be to Bryn-y-Neuadd. It was to have a relatively commodious goods yard to handle the considerable quantities of equipment and materials brought to furnish and supply the estate, much of which came from the Works at Oldham. Also, he found there was no church at Llanfairfechan where he and his family could worship in English as other people of English origin, who had preceded him, had found. The services at St Mary, the parish church, were conducted exclusively in Welsh because the vast majority of the parishioners was solely Welsh speaking. Already, the English people had subscribed to a fund, with Richard Luck playing the leading part, to build a second church in Llanfairfechan where they could have the services conducted in English but, at the time of John Platt’s settlement in the village, the fund was still short for building to commence. John Platt came to an arrangement with these people that he, entirely at his own expense, would build the church and the moneys so far subscribed would be used to endow it. He commissioned George Shaw — the noted Saddleworth architect, already responsible for Ashway Gap House and other commissions for him — to draw-up the plans which were to include for a striking spire. He provided the land which lay at a short distance, across a small field, from the Front Lodge at Bryn-y-Neuadd. A carriageway was made across the field to lead into the drive which was to encircle the church — an arrangement to avoid the horses and carriages having to be turned. This arrangement was a repeat, in much more picturesque surroundings, of the one which existed at St Thomas Church, Werneth, in the building of which church John Platt had been involved some ten years earlier. (A model of the Werneth church was preserved by the Platt family). The second church at Llanfairfechan was completed in 1864 with the Platt family pews placed at the extreme east end of the south aisle. John Platt had presented the organ, with which he had coupled the undertaking to pay the organist’s salary, and Alice Plait had presented the communion plate and the whole of the church Furniture. The church was called Christ Church and was consecrated by the Bishop of Bangor in the August, the event being followed with a celebratory luncheon at Bryn-y-Neuadd.

Lord Penrhyn, John Platt’s near neighbour to the west, and the other great landowners of Caernarfonshire, initially, must have had misgivings about this self-made man who had settled in their midst. The source of his undoubted great wealth was industry which, if not a cause for distaste, had, at least, to be regarded with caution for such was the convention of the day. Above all, these great landowners were Tories of the most diehard ilk and for them John Platt’s political views must have been alarming in the extreme. But John Platt soon came to be recognised as a man of sound vision and impeccable integrity and was accepted into their ranks, so that within the first four years of his entry into Caernarfonshire life he was made a justice of the Peace and Deputy lieutenant and, in 1863, held the office of High Sheriff of the County.

Chapter

VII - Sudden Changes

In the Spring of 1872 work commenced on considerable alterations and extensions to the House at Bryn-y-Neuadd. It was not possible, therefore, for John and Alice Platt to be in residence that season, instead, they, with one of their daughters and a niece, embarked on a tour of Italy, one purpose of which was to obtain new items of furnishings for Bryn-y-Neuadd. At Turin, John Platt contracted a chill, and although the party made every haste for home, the affliction developed into pneumonia so that, on reaching Paris, the party was forced to stay its Journey in the Hotel Maurice in the Rue de Rivoli. There John Platt died on the 18 May, he was only 54.

The townspeople of Oldham received the news in the vein of a family bereavement. Obituaries were generous with their words in recalling to memory the widespread benefits John Platt had brought to the town through his company and by way of the energetic and unfailing public services he had rendered. Alice Platt was presented, on 29 May 1872, with an illuminated letter of condolence, arranged in book form, from the Mayor, Alderman and Burgesses of the Borough of Oldham. John Platt was buried in a surprisingly modest tomb in Chadderton cemetery. The tomb bears the simple inscription: “Beneath this tomb lie buried the remains of John Platt, MP for Oldham, died Paris 18 May 1872, aged 54, Requiescat in Pace”. Six years after his death a bronze statue, mounted on an imposing marble plinth, was erected in his memory, close to the front of Oldham Town Hall, which, in later years, a less remembering generation chose to relegate to Alexandra Park. Yet, many of the torches he lit for the benefit of Oldham, especially in the field of technical education, were to be kept aflame by others he had inspired and by the great Company he had owned. The death of John Platt posed no serious difficulties at the Company for Samuel Radcliffe Platt, who had been well and truly schooled by his father, instantly took the helm, though far earlier than he had expected to he called to do.

In Llanfairfechan, and in the wider county of Caernarfon, the shock and grief at John Platt’s death was equally felt. Locally, it had been anticipated that after John Platt’s death Henry Platt would transfer to Bryn-y-Neuadd, which estate it seemed John Platt had regarded as the family seat, and Alice Platt would retire to Gorddinog as the dower house. In reality, well before John Platt’s death, matters had been decided otherwise. Alice Platt preferred to live in Oldham and it was understood, if widowed, she would make Werneth Park her home, which she did for a further thirty years. Henry Platt’s prime interest was agriculture and he remained at Gorddinog, which had already been conveyed to him in his father’s lifetime, since that estate had every advantage over Bryn-y-Neuadd for such an interest. Sam Plat (as he was known to the Family, with his commitments in Oldham, also dwelt at Werneth Park. The third son, Frederick Platt, shortly to marry, chose to settle at Barnby Manor in Nottinghamshire. Bryn-y-Neuadd was, therefore, left unoccupied and the other sons, as they came to need a residence, showed no enthusiasm for the place, preferring to find homes in Cheshire, Flintshire and Bedfordshire, some with secondary homes in London, at fashionable addresses. James Edward Platt, the sixth son, acquired a villa on the French Riviera — Villa Annunciata Californie, at Cannes, as a retreat in which to spend part

of his tine. Consequently the Bryn-y-Neuadd estate was offered for sale but there were no takers. Despite this set-back, the estate remained, under the eye of the Agent, fully manned and kept up and, from time to time, some members of the Family would stay there, but no further developments were undertaken in the House nor on the estate generally. Then, in 1884, John Platt’s youngest son, Sydney, who had been only eleven years old when his father died, and his young wife Bertha (nee Marshall) decided to make their home at Bryn-y-Neuadd. This decision was cause for great joy and celebration in Llanfairfechan and when the young couple arrived in the village, on Christmas Eve, their carriage was drawn by estate workmen in a procession, headed by a band, from the railway station to the house. A few days later a banquet was held, for all walks of life in the village, to express the universal satisfaction felt at there being, at long last, permanent residents at Bryn-y-Neuadd. For over thirteen years Sydney and Bertha Platt entered into the life of Llanfairfechan; he was the leading figure in the building of St. Winifred’s School for Girls. Nevertheless Bertha Platt never wholeheartedly took to living at Bryn-y-Neuadd so that in 1898 the couple decided to leave. Again the estate was put up for sale, this time successfully, and so just forty-one years after John Platt had bought the Roberts lands the Platt association with Bryn-y-Neuadd ended.

Apart from the cessation of developments on the Bryn-y-Neuadd estate itself, two major projects, partially outside its boundaries, were abandoned after John Platt’s death. The first was the direct private carriage drive from Bryn-y-Neuadd to Gorddinog. As matters had stood, when travelling from the House at Bryn-y-Neuadd to the House at Gorddinog it had been necessary to leave Bryn-y-Neuadd Park at Grand Lodge and pass along the Turnpike road to enter the grounds of Gorddinog at Main Lodge. The plan for the new carriage drive (which, in the reverse direction, was also intended as a more convenient route for Henry Platt to attend Christ Church) had been to leave Bryn-y-Neuadd Park at Front Lodge, cross over the Turnpike road and proceed in a much shorter line, entirely over Platt land, to enter the immediate grounds of Gorddinog at East Lodge. Work had actually started at the Gorddinog end where an impressive sweeping entrance to the drive had been constructed in front of the house — The Oaks — in which the Agent to the Gorddinog estate was to live as also, at that point, had an ornamental drinking trough for the horses and dogs. From the entrance, the foundations for the carriageway had been excavated for some distance towards Bryn-y-Neuadd.

The second, and by far the more significant, project to be abandoned was the provision of a dock and pier at Llanfairfechan to accommodate the sea going steam yachts of three of John Platt’s son’s: Henry Platt’s Jessie”, Samuel Radcliffe Platt’s “Norseman” and Frederick Platt’s “Jeannette”. Parliamentary approval had been needed for this project and, in 1872, progress was well advanced. A Board of Trade provisional order had been granted, plans had been deposited with the Clerk of the Peace in Caernarfon and a house “Moranedd”, supporting a lantern rower, had been built at the mouth of the Llanfairfechan river.

John Platt, except for the specific bequests to his wife, Alice, of a sum of two thousand pounds (for her immediate contingencies upon his death), his jewellery and various of his effects in the House and about the grounds at Werneth Park, left his real and personal estate to his trustees (who, also, he made his executors), his three eldest sons: Henry Platt, Samuel Radcliffe Platt and Frederick Platt and his two sons-in-law Thomas Hardcastle Sykes (the husband of his eldest daughter, Mary) and Joshua Walmsley Radcliffe (the husband of his second daughter, Lucy Jane) entailed to their heirs, executors, administrators and assigns under direction for certain provisions to be made for his daughters and his other four sons (these Sons when the Will was made were minors and were still so at the time of his death) and the children of any son or daughter who might have predeceased him. The statutes ruling in 1872 did not require a valuation of an estate to be included with the Probate of a will but the measure put by the Family on John Platt’s fortune was six and a half million pounds. ‘The Will declared that Alice Plait was to be allowed to live free of rent at Werneth Park but she was to be responsible for the payment of all rates and taxes, insurance premiums and the repair and maintenance costs on the property. Her income, of £2000 per annum, was to be provided either out of the interest on John Platt’s ‘residuary trust property” or from the purchase of an annuity according to which option the Trustees deemed preferable. Apropos the provisions directed for his sons and daughters John Platt instructed that any advances he had made or any extraordinary expenditure he had incurred for the ‘advancement in life”, of any son or daughter, and so recorded in his Private Ledger, the amount involved was to be debited against the share due to that son or daughter. Notwithstanding this general instruction, an explicit contrary instruction was given that the Gorddinog estate was not to be debited against Henry Platt’s share. Under the Will the Trustees were empowered to act in the widest possible way, as they saw fit, in the matter of the shares in Platt Brothers & Company Limited.

Chapter

VIII - Gorddinog — Colonel Henry Platt

The Gorddinog estate which John Platt had bought, like Byrn-y-Neuadd, was in a state of some neglect. It had been the ancestral home of a long-standing Welsh family which had died out. In the interim, a Mrs Crawley had occupied the House before she married the Rector of Llanfairfechan, Mr Vincent, who, later, was to become the Dean of Bangor. John Platt had regarded the House to be antiquated and had decided it had to be demolished and replaced with a befitting new mansion. The new mansion was built entirely from local granite with an air of the Elizabethan style of architecture. It had been realised, if the new mansion was positioned further up the natural slope of the ground, than where the original house had stood, the area then made available, in front of the new mansion, could be landscaped. However, to do this required the course of a small river (Nant y Felin fach) to be diverted from a point behind the intended site for the new mansion. Additionally, John Platt had decided that if the diversion of this river was continued all the way to the sea, a distance of almost three quarters of a mile, such that it passed through the western end of Bryn-y-Neuadd Park, the Park would be enhanced. A granite lined open culvert was constructed (on a line to the east of the river’s natural course) which ran through Gorddinog land until it reached the Turnpike road, thence under the road into Bryn-y-Neuadd Park, close to Grand Lodge, where natural looking ponds were made in its course. The acreage of the Gorddinog estate was far greater than the acreage on which John Plait had developed the Bryn-y-Neuadd estate, respectively some 1100 to 330. Not only did Gorddinog contain more pasture and arable land but it had a large expanse of hill land over which a substantial flock of the native Welsh sheep could be run. The lower hillsides, directly behind the House, were planted as woodland in which was included a cluster of exotic trees from overseas, as was the then fashion, and masses of rhododendrons, in a variety of colours, which in the spring and early summer formed a breath-taking backdrop to the House. In every respect, Gorddinog was a superior estate to Bryn-y-Neuadd.

There was no park, in the classic sense, at Gorddinog, the immediate grounds to the House, as intended, took every advantage of the natural slope of the land for rolling lawns, studded with trees, and formal gardens to be laid out which had, as the centre piece, a large pond, stocked with trout, set in the course of the diverted river. Walks were made through the woodland and, to cap all, a grand carriage drive was constructed through the woodland and out onto the open hills such that it wound round the crest of the highest hill, resulting in a circular tour, of close on two miles, offering splendid views of the sea and mountains from every direction. The drive was known as John Platt’s Walk. At one point, when constructing the drive, the carriage way had to be hewn through solid rock which, it was noticed, was iron ore bearing. Conscious, as ever, of the need for Platt Brothers & Company to be, wherever possible, self-sufficient in all things John Platt had a business-like sampling shaft sunk into the hillside. The analysis of the samples showed the ore to be of insufficient grade for commercial exploitation and no further interest was taken, hut the shaft and spoil heaps remain, albeit now shrouded in bracken.